CarbonQuest wants to take a bite out of carbon emissions at its source — before the greenhouse gases escape into the environment and heat up an ever-warming planet.

The Spokane, Wash.-based startup is building devices that are paired with smaller natural gas operations such as gas boilers, fuel cells and industrial activities.

Carbon capture technology for industrial sites isn’t new, it’s just typically applied to bigger facilities such as large power plants.

“We saw this as a really big problem and really big opportunity.”

– Shane Johnson, CarbonQuest co-founder and CEO

But the small emitters are much more numerous, with about about 800,000 distributed emission sources in North America alone.

“We saw this as a really big problem and really big opportunity,” said Shane Johnson, CarbonQuest co-founder and CEO.

CarbonQuest is among a growing number of carbon capture technology startups helping companies adhere to climate goals and emissions regulations.

The team developed its own technology to capture the carbon with a filter that includes a solid, non-toxic sorbent material. The device can pull out approximately 90% of the CO2 from an emission source’s flue.

By the end of this year, the company expects to have six carbon capture systems installed in New York City and Johnson said there are more than 100 projects in the pipeline.

“Distributed, smaller consumers is something that we haven’t thought about very much,” said Grigorios Panagakos, an assistant professor in chemical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University who researches carbon management. “That’s something that is kind of unique as an application.”

There are 14 investment-backed companies internationally working on point source carbon capture, according to a new report from PitchBook. Others include British Columbia-based Svante, Carbon America, ReCarbon and Ardent. The sector raised more than $1.2 billion from investors from 2018 through the first quarter of this year.

A closely related field — removing carbon from the atmosphere using so-called direct air capture (DAC) devices — raised an additional $1.7 billion over that period.

Building demand

The carbon capture sector has been growing, but still faces market challenges. There are few entities are required to significantly curtail their carbon emissions, and uses for the captured carbon are limited.

U.S. states have a patchwork of policies and targets aiming to reduce carbon emissions. Washington and California having implemented the most aggressive programs, though Washington’s climate regulations will be scrapped if voters approve a controversial initiative in November.

Corporations such as Amazon, Microsoft and many others worldwide have voluntarily committed to shrinking their climate impacts. Through those commitments, the corporations can pressure other companies with whom they do business to also cut their emissions.

But given that carbon reductions are optional for many, the price of removing the pollutant needs to pencil out for companies doing business with startups such as CarbonQuest.

CarbonQuest’s goal is to get the cost down to about $75 to $175 per ton of carbon captured — which is much cheaper than the $600 or more per ton that it costs to suck the carbon out of the atmosphere. The price of the machinery, operations and maintenance, and energy use all contribute to the per ton costs, Johnson said.

The U.S. government has created incentives to bolster the carbon removal market, which benefit CarbonQuest and others. In 2018 the U.S. created tax credits for carbon capture, and in 2022 lawmakers more than doubled those incentives through the Inflation Reduction Act.

Industrial and power generating facilities producing at least 12,500 tons of CO2 a year can now receive credits of $85 per ton for carbon that is captured and permanently stored in geologic formations, or $60 per ton if the captured carbon is diverted to other uses.

There’s also the potential for selling carbon offsets in which one entity pays another to remove carbon in order to reduce the buyer’s carbon footprint. The Biden administration this week issued government guidelines around offsets.

Captured carbon

Then there’s the question of what you do with the CO2 after it’s captured.

The carbon can be permanently sequestered in concrete or converted to rock in geologic formations. It can also be used for industrial processes, such as carbonating beverages, as feedstock for plastics, and to make sustainable aviation fuels. The CO2 can even be used for more fossil fuel extraction. But many of these technologies and markets are still being developed and there’s more carbon available than there is demand for it.

“It just doesn’t scale,” said Panagakos, of Carnegie Mellon. “So we’re thinking, ‘OK, what can we do?’ It would be absolutely fascinating if we had efficient ways to convert it into something useful.”

Johnson said they’re casting a wide net for partners who want the carbon, with an initial focus on companies incorporating it into concrete. At this point, he said, the volumes of CO2 being produced by their systems are manageable for offloading.

But the business is prepping for growth. CarbonQuest has been largely self-funded since launching in 2019, and is now pursuing outside investors.

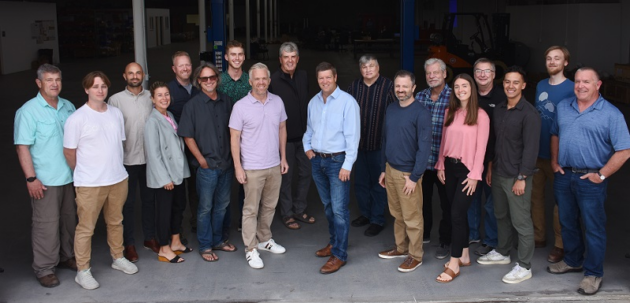

The company is the third Spokane-based startup for Johnson and a core team of founders. The group’s first business was World Wide Packets, a telecom company that they sold in 2008 for about $290 million. That was followed by Demand Energy Networks, a distributed power storage business that Enel acquired in 2017 for about $250 million.

Johnson is bullish on his home city as an innovation hub.

“There’s a growing and thriving entrepreneurial community — and especially in the clean energy and clean tech space — in Spokane,” Johnson said.

CarbonQuest has 23 employees, with its engineers based in Spokane and a commercialization team in New York City.

‘It’s indispensable’

“If we want to mitigate emissions of CO2 with a financial burden that is realistic or that we can bear, we need carbon capture [and] sequestration.”

– Grigorios Panagakos, assistant professor in chemical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University

Demand for clean energy solutions is rising thanks to the increased electrification of transportation and other sectors, combined with expanding data center operations that are supporting the use of artificial intelligence.

More wind and solar plants are being built, but those renewable sources need to be matched with energy generation that happens 24/7. That could be giant batteries, nuclear power, geothermal and other options — but will likely include natural gas, at least for some time. And there are industries that emit CO2 during their production processes, including cement, steel and some chemical manufacturing.

“If we want to mitigate emissions of CO2 with a financial burden that is realistic or that we can bear, we need carbon capture [and] sequestration,” Panagakos said. “So it’s indispensable.”

However, some people raise concerns that carbon capture simply prolongs the use of oil and gas, and fossil fuel companies are strong supporters of the technology. Others — Johnson included — argue it can help address carbon impacts right now in difficult to abate sectors and situations.

“We can come in and be a part of this energy transition story,” he said, “and meet that need.”