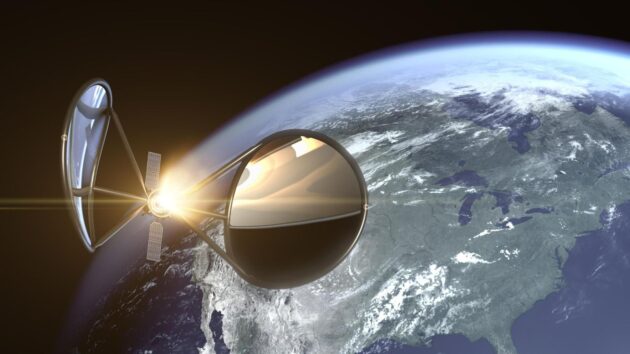

A Seattle-area startup called Portal Space Systems is emerging from stealth to share its vision for a type of satellite that’s apparently never been put into space before: a spacecraft that uses the heat of the sun to spark its thrusters.

The technology, known as solar thermal propulsion, could be put to its first in-space test as early as next year.

“I’m not aware of anybody that has flown any system with solar thermal propulsion, in the U.S., or foreign for that matter,” Portal co-founder and CEO Jeff Thornburg told GeekWire. “I mean, it could have happened, but maybe no one’s aware of it.”

Bothell, Wash.-based Portal says it has already been awarded more than $3 million by the Defense Department and the U.S. Space Force to support the development of its Supernova satellite bus. In space industry parlance, a bus is the basic spacecraft infrastructure that supports a satellite’s payloads.

Supernova-based satellites would be equipped with a solar concentrator apparatus that focuses the sun’s rays on a heat exchanger. “It’s a very simple system,” Thornburg said. “You pass your monopropellant through a hot heat exchanger, and out comes thrust.”

The technology has the potential to give satellites much more mobility in orbit — which could smooth the way for applications ranging from rounding up orbital debris to responding to international crises.

“We have high performance and high thrust, which means we can get places faster than spacecraft with electric propulsion solutions, which are predominantly the propulsion system of choice,” Thornburg said.

The spark of an idea

Portal’s solar thermal propulsion system is only the latest in a string of innovations that Thornburg has worked on.

He played a pivotal role in the development of the methane-fueled Raptor rocket engine that powers SpaceX’s Starship super-rocket. At Stratolaunch, the space company founded by the late Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, Thornburg worked on a 3D-printed rocket engine known as the PGA (which were Paul G. Allen’s initials). He served as the director of mechanical engineering and manufacturing for Amazon’s Project Kuiper satellite development effort in 2020-2021, and then took on lead engineering roles at Agility Robotics and Commonwealth Fusion Systems.

Thornburg’s interest in nuclear propulsion led him to consider solar thermal propulsion, which had been the subject of research at NASA and at the Defense Department as far back as three decades ago.

“I think the future of propulsion is nuclear thermal propulsion, in my lifetime anyway. But I can’t go to Lowe’s and buy me a fission reactor yet,” Thornburg said. “So I was like, ‘What would be close? Or what would be a step in that direction?'”

Thornburg said he went looking for propulsion technologies “that the U.S. government has already put a ton of money into, that are sitting on the shelf with the Ark of the Covenant, that I could innovate around and bring some solutions faster as a small company.”

Solar thermal propulsion looked like the best option. “It’s taken me back to my SpaceX Raptor days, where we can move fast and break things, and iterate more quickly,” he said. “And we had a good scientific foundational base to justify our performance estimates, because of all the work that the government had done 30-plus years ago.”

Portal isn’t the only space venture looking into solar thermal: Arizona-based Howe Industries is also working on the technology, but for pint-sized nanosatellites that would turn water into steam to power their thrusters. Portal’s system would kick solar thermal propulsion up to a much higher level.

Small steps and giant leaps

Solar thermal’s ability to deliver high-performance propulsion for in-space mobility is a huge selling point. The Supernova satellite bus, which has a mass of about 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds), is designed to provide up to 6 kilometers per second of delta-v. (Delta-v is a measure of how much a spacecraft can change its velocity.)

“A lot of systems are lucky if they have 200 meters per second of delta-v when they launch. Certainly most have 500 meters per second or less,” Thornburg said. “So, we’re talking about 10X the capability of existing systems. And then when you add refueling on top of that, now you’ve really got a game-changer, with multiple of these spacecraft in particular orbits servicing certain needs.”

What happens when the satellite goes where the sun doesn’t shine — for example, when it’s flying over Earth’s night side? “We’re actually working on another aspect of design where we can operate the thruster independent of where the sun is,” Thornburg said. “You can think of it as having a thermal battery.”

The Pentagon is interested in solar thermal because it fits into its “Tactically Responsive Space” strategy, the idea that space assets will have to be rapidly deployed to respond to global threats. Portal was one of 18 companies selected to receive $1.7 million contracts to work on technologies that could “propel the U.S. Space Force toward future responsive and dynamic space operations” by 2026.

Thornburg said Portal is on track to meet the Pentagon’s schedule.

“We have a relatively high TRL [technology readiness level] across Supernova even before we’ve flown our first demonstration,” he said. “But our first demonstration, when we fly it in late ’25, will really be validating the integration of all those systems, plus our proprietary heat exchanger designs that we’re bringing to the party.”

The Supernova satellite bus can be used for commercial applications as well. The mobility that comes with solar thermal propulsion could be attractive for companies that want to redeploy their satellites in different orbits, or rendezvous with other spacecraft for refueling or debris removal. But Thornburg doesn’t want to get too specific about what Supernova could be used for.

“When we looked at the market, there are some companies that say, ‘We’re going to be an orbital debris company, or we’re going to go map the debris and monetize that.’ I didn’t think there’s enough real revenue long-term in any one of those distinct areas to build a business around,” he said. “But I did think that all of those businesses want more delta-v than they have capable. So, we market it as a satellite bus structure, because we can offer so many different opportunities to allow folks that are focused on their unique payload application.”

The road ahead

If Portal is successful, the company will add to the Seattle area’s already-formidable array of satellite manufacturing operations. SpaceX’s Starlink satellite development and manufacturing facility is in Redmond, and Amazon’s Project Kuiper satellite operation is based in Redmond and Kirkland. Redmond is also where Xplore is working on its Xcraft satellite platform, while LeoStella builds satellites in Tukwila. Starfish Space (in Tukwila) and Lumen Orbit (in Bellevue) are also part of the mix.

Seattle’s status as Satellite City is a factor in the choice to put Portal’s headquarters in Bothell, but not the only factor. “My wife and I came out here during the pandemic and have no intention to ever leave,” Thornburg said. “So, I needed to build the business here in Seattle for a lot of different reasons, more than just business ones.”

Thornburg said that about 25 people currently work at Portal’s offices, and that the company is aiming to put its Supernova production facility at a location somewhere in the Bothell-Marysville-Arlington area. “We’re pretty excited about that,” he said. “I see us growing from where we are with 25 to probably 100 in the next year, and looking at probably growth up to 150 or 200 people over the next 24 months or so.”

Portal’s other co-founders also have previous connections to the Seattle area’s space industry. Chief operating officer Ian Vorbach, an aerospace engineer who has gravitated toward early-stage startups, briefly worked for Stratolaunch when it was headquartered in Seattle. Prashaanth Ravindran, who is Portal’s vice president of engineering, previously worked at Stratolaunch as well as at Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space venture in Kent, Wash.

Some things about Portal are still up in the air: For example, the company hasn’t yet announced its plan for launching next year’s demonstration mission. “We have a few different options that we’re chasing — some that we would be taking on, on our own, and some that potentially would be in partnership with the U.S. government,” Thornburg said. “Those conversations are happening in real time right now.”

Thornburg is also keeping mum about the identity of Portal’s strategic investors, and about how much money they’re investing — other than to say that Portal has “the right amount of funding” to conduct the demonstration mission.

“Too many people now think that the measure of a company’s success is based on how much money it’s raised,” Thornburg said when those questions were asked. “That is the wrong metric. … I am so personally fatigued by that being the measure of success out there that I want to show people that that is not the most important factor in whether a space company is going to be successful or not.”

So, what’s the right metric? Thornburg pointed to the trust and financial support that Portal has received from the Space Force. “I’m looking forward to making them more successful — and giving the country that capability it wants to have,” he said.